Rights Holder Voices at the UN Forum on Business and Human Rights - Part 2: The Data

This is the second in a short series on rights holders at the UN Forum on Business and Human Rights. Over the past four years, rights holders have comprised only 6% of the speakers at the Forum. In my last post, I explained that this matters because rights holders have unique perspectives and expertise that are essential for the constructive dialogue and cooperation that the UN Forum seeks to promote. In this post, I am going to examine data on the stakeholder groups that participate in organizing sessions, the geographic diversity of speakers at the Forum, and the breakdown of speaker categories over the past four years. My aim is to spark conversations and action that will make the UN Forum better, as well as open up a broader conversation about rights holder agency and the importance of rights holders’ ideas and contributions.

First, a quick note on the methodology. My last post explains the speaker data collection in detail, and the underlying data and detailed methodology are available for those who would like to explore it further. So here I’ll just add that I also collected information from the online session descriptions, including the session organizers and whether interpretation information was provided. If a session had multiple organizers, every organizer was categorized, employing the same categories used for speakers, described in detail here. In total, data was collected on 246 sessions at the UN Forum from 2018 - 2021, including all formats. Of those, 70% included information on the organizers.

As a side note, only 114 sessions – less than half (46%) of them – contained information on interpretation. I do not know if that means no interpretation was provided, or if the organizers simply neglected to include that information in the session description. I can say, where information was available, interpretation was predominantly provided in English (85 sessions), French (80 sessions) and Spanish (62 sessions). By comparison, there were only 4 sessions with Chinese interpretation, and only 5 with Arabic.

Session Organizers at the UN Forum

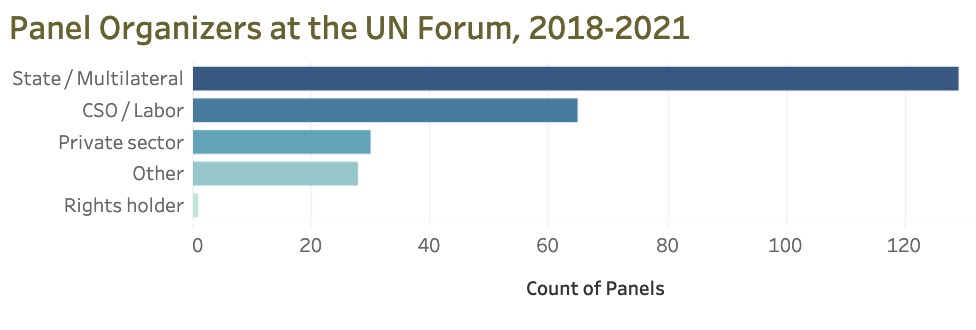

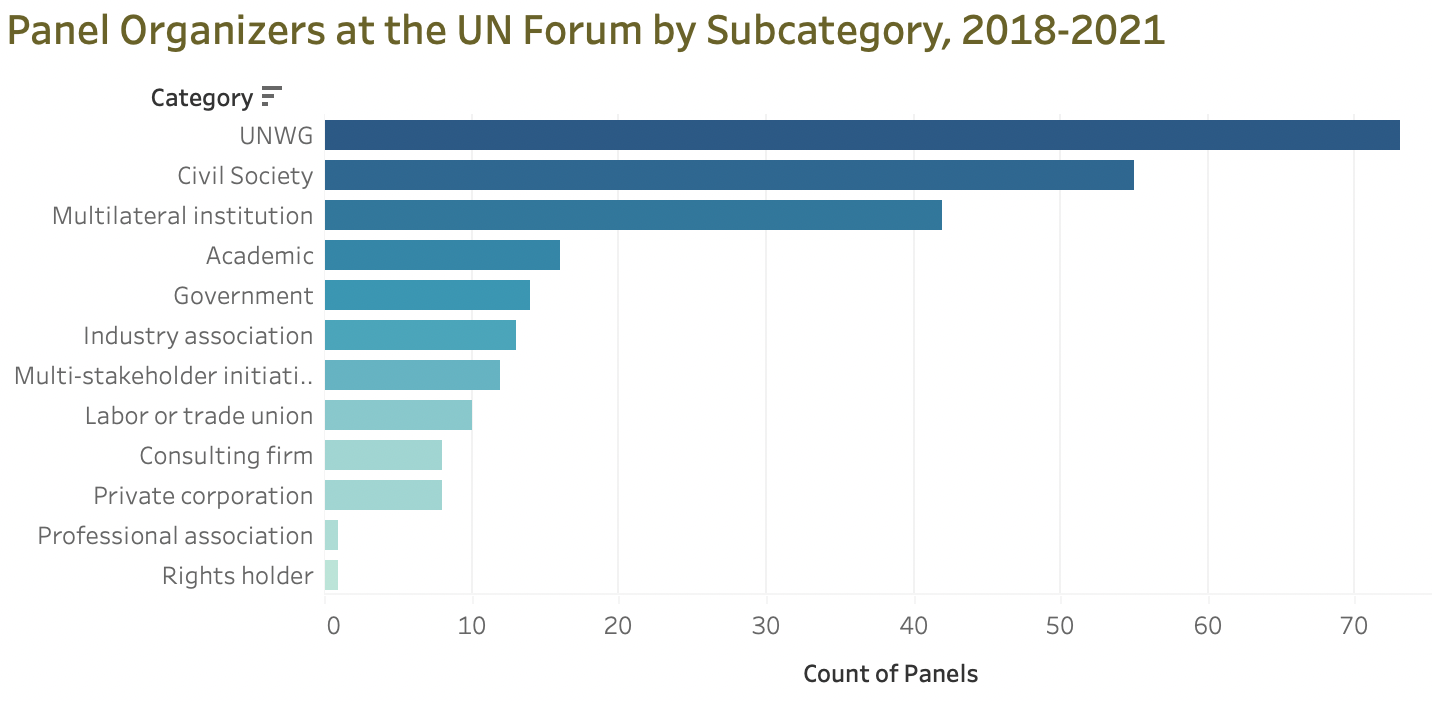

As the charts below show, sessions at the UN Forum are collaborative efforts. As Tara Van Ho explains in her blog series on academics at the UN Forum, before the COVID-19 pandemic, stakeholders sent proposals to the Working Group, who then selected panels and in some cases suggested other stakeholder groups to jointly develop the panel and to choose the speakers. This likely explains the large number of panels that civil society played a role in organizing.

While the process is less clear since the UN Working Group has stopped soliciting session proposals, the data suggests that civil society continues to play a big role. This can be seen in the breakout of organizers by subcategory in the second slide, below, which shows that, apart from the UN Working Group, civil society organizations have been the most involved in shaping session content, more so than multilateral institutions even.

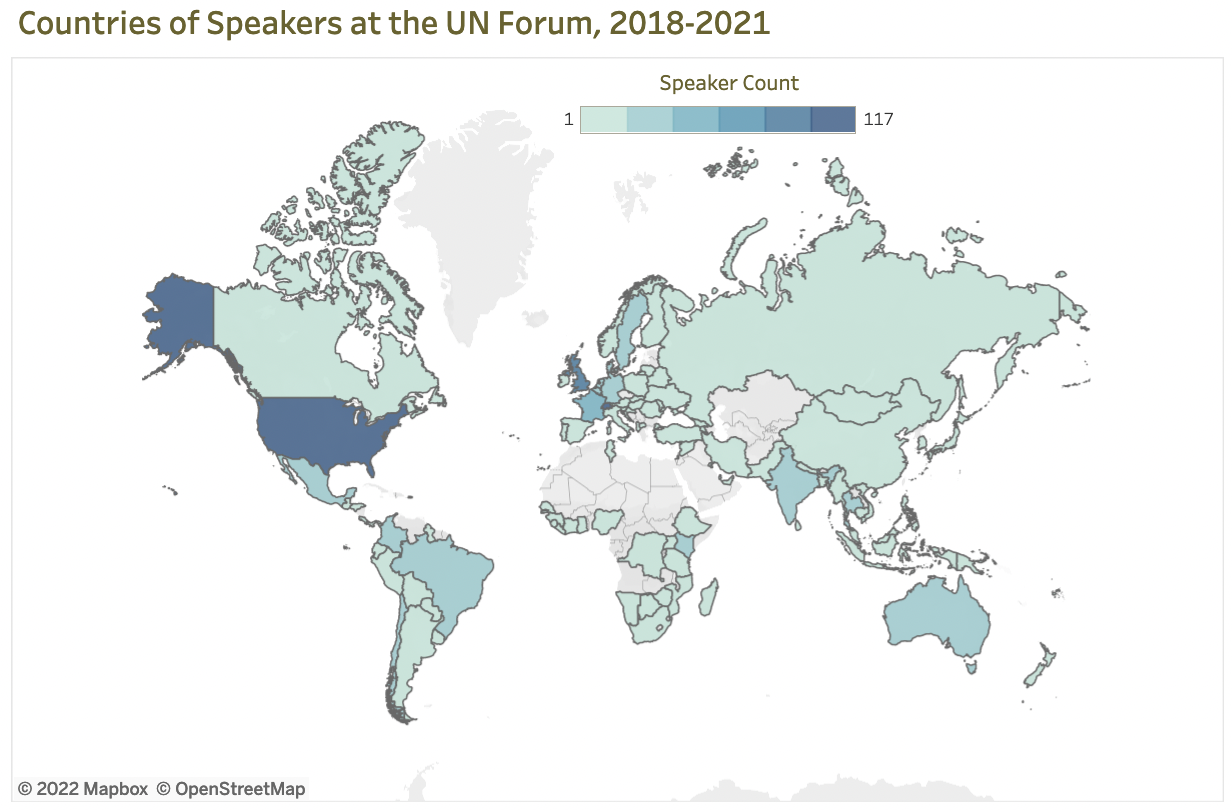

Geographic Diversity of UN Forum Speakers

I want to start here by acknowledging that the UN Working Group organizes a series of regional business and human rights forums, and that I have not analyzed the speaker breakdown at those events. It could well be that the regional forums are more hospitable to rights holders for a variety of reasons. But that does not excuse the fact that so few rights holders have appeared as speakers at the main UN Forum, which is, in the words of the organizers, “the foremost event to network, share experiences and learn about the latest initiatives to promote corporate respect for human rights.”

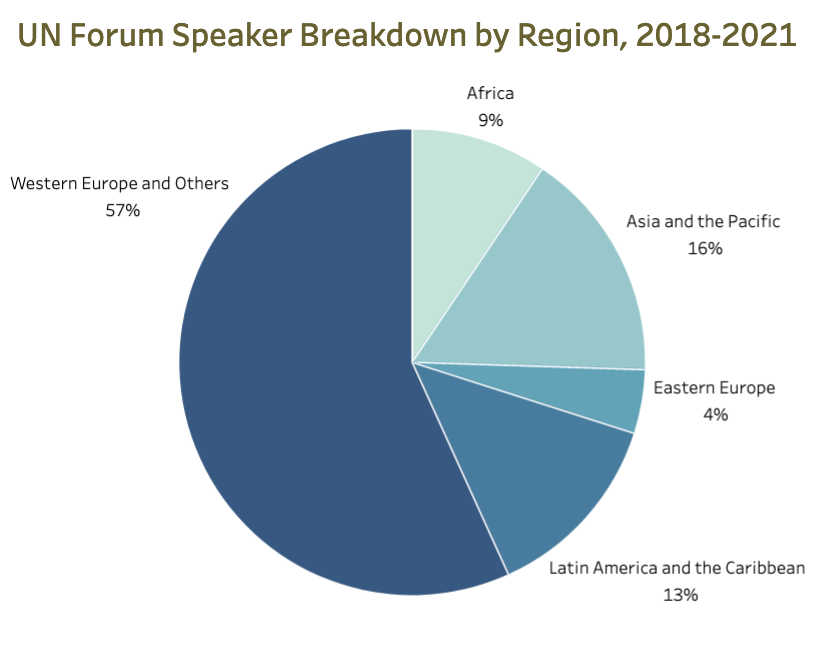

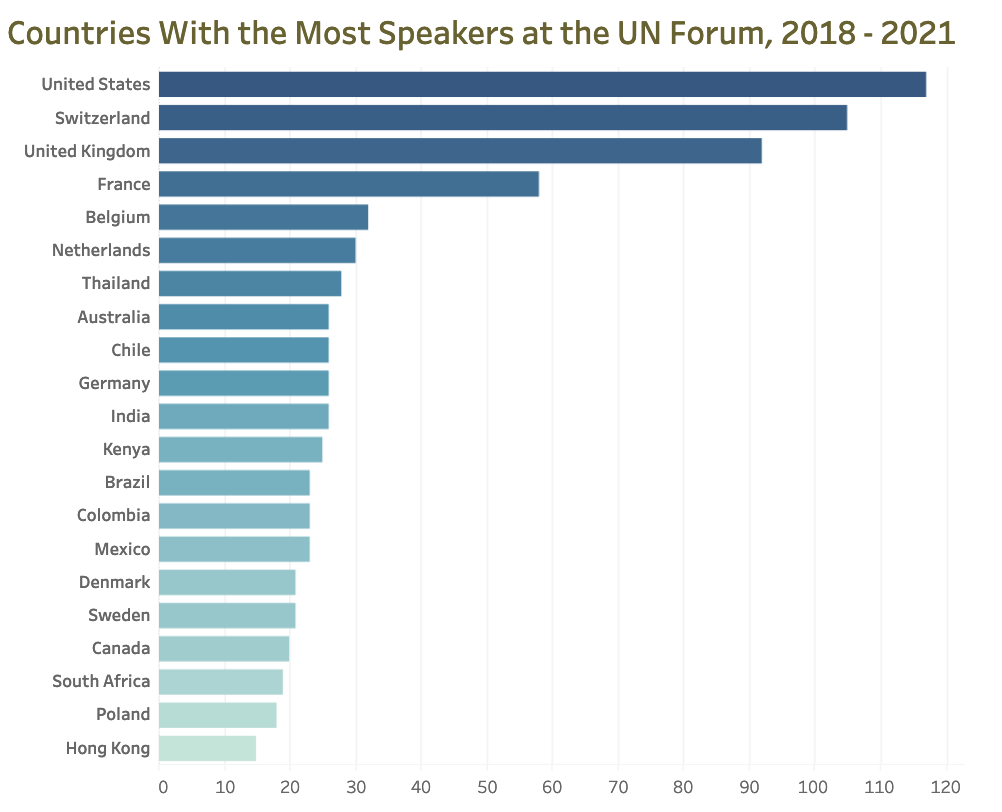

As these charts show, the majority of the speakers at the UN Forum over the past four years have come from the United States, the United Kingdom and Western Europe. (For the breakdown by region, I used the United Nations’ regional groupings of member states, which includes the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia in “Western Europe and Others.”)

One thing that I immediately thought about as to why more rights holders are not speakers at the UN Forum is the travel and expense involved in attending an event in Geneva. The data seems to bear this out somewhat, as speakers from relatively wealthier countries have made up the majority over the last four years.

The data could also speak to difficulties in obtaining visas, particularly if the Forum organizers do not provide letters early enough to facilitate speakers obtaining their visas in time. (The Forum information for this year, for example, does not yet include information on who will be speaking, despite that the event is next month.) Visas are also impossible for people without passports or documentation of legal status in the states where they currently reside.

It is also important to bear in mind that most of the top countries in terms of sending speakers to the Forum are host states for multilateral institutions (the United Nations in the United States and Switzerland; the European Union in Brussels; the OECD in France) and all of them serve as headquarters for multi-stakeholder initiatives or international human rights NGOs. This suggests that traditional centers of power impact who speaks at the UN Forum.

Yearly Breakdown of UN Forum Speakers

Another indicator that it is not just travel hurdles at play is the fact that, when the UN Forum shifted to a virtual format in 2020 and 2021 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the percentage of rights holder speakers decreased or remained the same.

All of which suggests that entrenched disparities in relation to access to power and influence are at play. These disparities play out in countless ways, from what kind of knowledge is valued and who knows who at those international institutions, to how easy it is to reach someone quickly by phone or email or how much time people have to participate in developing a session (in light of organizational or family responsibilities).

The fact that these disparities are deeply rooted is not a justification for sidelining rights holders at the UN Forum. In fact, the UN Human Rights Council resolution establishing the Forum on Business and Human Rights requests that the OHCHR provide the necessary support to convene the Forum, “giving particular attention to ensuring participation of affected individuals and communities.”

But I should be clear that the purpose of this research is not to blame the UN Working Group or the Secretariat staff who help organize the Forum, who may indeed be taking steps to add more rights holder voices, as suggested by the UN Forum theme this year Rights Holders at the Centre. As I said at the outset, my intention is to explore ways to improve the representation of rights holders as speakers at the UN Forum, and other important debates and convenings in the business and human rights field. Without better efforts, the UN Forum, and the business and human rights field itself, risk perpetuating the systemic disparities they should be seeking to confront.

Rather than posit solutions myself, I’ve reached out to past rights holders at the UN Forum and others to ask what they think — and I invite your comments here, through our contact us page or on twitter at #UNForumBHR.